Dena El Saffar on her listening practices

You can also read the article here: “Dena El Saffar on her listening practices” Muslim Voices. February 25, 2022

“To really have the spirit of the Middle Eastern music, you shouldn’t be looking at a piece of paper . . . you should be looking at each other or closing your eyes or looking at your instrument.”

Right before the pandemic, Dena (the founder of Salaam) and I have been practicing for an upcoming Turkish concert. After our rehearsals, I often hang around and find myself in an engaging conversation with her. On one of those days, she kindly sat down and answer some of my questions about representation issues. Although the global health crisis did not allow me to complete this project, I nevertheless learn valuable insights and lessons from Dena. Here, I share some of her comments and reflect on my own experiences as a Turkish female musician.

Dena El Saffar and Tim Moore. Credits: salaamband.com/

Whether subtle or obvious, the stage harbors multiple meanings. Presentation, performances, instrumentation, and many other components play significant roles in constructing cultural imaginaries. But where do we draw the line between representation and exploitation? This question becomes especially important for vulnerable groups such as the Middle Eastern communities in the United States. Given the mainstream media’s long history of stereotyping and othering the Middle Eastern people, how do we represent the Middle Eastern musical traditions without manipulating or commodifying them?

As an international student at Indiana University, I feel both lost and chosen. I am lost because I am continually adjusting to things that many of my peers take for granted in their everyday life. Still, I feel chosen because I see the opportunities that I was given to have a degree and do research. Performing with Salaam in 2017 was one of these opportunities that were presented to me as a Turkish bağlama player.

Salaam is the only Middle Eastern music band in Bloomington, Indiana. Since its founding in 1993, Salaam members have performed on various platforms with international artists from various regions. The diverse background of Salaam members creates a colorful repertoire from traditional Egyptian music to flamenco of Spain.[1] The name “salaam” is also a well-thought band name: it mirrors their core purpose, which is to be “a musical ambassador for peaceful coexistence.”[2] Since I moved to Bloomington, I shared the intimacy and passion of being on the stage with its members as a guest performer. Observing their work ethic, stage preparations, and other seemingly simple details provided me with the amazing opportunity to dive into the world of Middle Eastern ensembles.

Dena: Finding the Balance

Dena is an Iraqi-American musician who was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. She is playing viola since she was in fourth grade. She earns her livelihood by teaching and performing on various platforms across the United States. Although Dena is classically trained as a violist at Jacobs School of Music and born into western culture, she understands and harmoniously incorporates two cultures in her life.

Despite her classical background, I have barely seen Dena using musical notation to practice our repertoire. When I asked about it, she told me that she decided not to write anything down and learn it by ear.

“Honestly, written music is really, really compromised. It is not a way to learn it. If you learned from the page and you played, it wouldn't sound like Iraqi maqam […] To really have the spirit of the Middle Eastern music; you shouldn't be looking at a piece of paper, you know, you should be looking at each other or closing your eyes or looking at your instrument.”

The practice of oral transmission (meşk) is the primary system of music transmission for most of the Middle Eastern traditions. Although there are specific notation system, I must say, they contain very limited information and often do not include the necessary nuances of the piece. Therefore, most musicians create healthy social relationships with their masters and transmit knowledge from generation to generation. The master-apprentice relationships among generations create a sort of belonging to the tradition. This transmission practice also challenges the compelling idea of autonomous individuality.

Image: Bedros Haroutunian’s qanun, April 22, 1939, collected by Sidney Robertson Cowell in Fresno, California. (Library of Congress)

Dena's comment about looking at people to have the spirit reminds me of my own experiences in Turkey, and how my teachers were asking me to follow my peers' eyes and watch for the cues and signals. Such an attunement on the stage allows me to become a part of a larger whole.Perhaps, focusing on multi-sensorial experiences (both on the stage and ethnographic research) shows us what we have in common.

Dena also finds a balance between both cultures in her professional life, where she can fluently practice two different musical traditions. Instead of applying Western norms to Middle Eastern music, she acknowledges the fact that there are different ways of learning:

“I love to play Bach. Everything is communicated perfectly from the page. Everything! It's so cool. I love that . . . . I got to play with this Arab orchestra in Detroit for a few years. And that's exactly the music that they play with, like a big violin section, and cellos and oriental instruments or whatever they call them, and it's fun, but it also seems so shallow at some point. It's just like there's no personal expression. It's all very kind of fake and glossy and you know, after playing this rootsy Iraqi music which is less famous and less understood. It helped me to get away from that kind of commercial music . . . . It was cute, but it's not deep. It's still out there for that kind of thing anyway."

What makes Dena fluent in Middle Eastern music is not only her musical ability but also her willingness to be immersed in listening and learning practices.

Dena, as a bicultural musician, is able to provide some background (historical and political information and a few musical terminologies), which gives adequate context for largely Western audiences. For example, in one of the noon lectures at the Archives of Traditional Music, Dena receives a question about women's representation in Middle Eastern music. She addresses the question, first, by listing a few countries (Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt) where women can play and perform music without any restriction, and then very eloquently reminds her audience that people and cultures are complicated:

"You know it is really complicated. It really is, and I've never had anyone tell me I should not [play]. Nobody's ever discouraged me […] it is a little bit of an issue now. But if you look back at paintings like Persian miniatures, I don't know if you ever have seen those, but there's a lot of depictions of women playing music. So, obviously, it's kind of comes and goes where along the lines of acceptability."[1]

As a Turkish female musician, I can’t tell how many times I received these kinds of questions. These comments or questions get incredibly annoying especially when I am on the stage with my instrument. While I am expected to be careful about slavery and race discussions in the US, I have to deal with this attitude considering Muslims as a monolith group. Also, these questions often suggest Middle Eastern women as victims of their culture. (If you want to read more on that check Do Muslim Women Need Saving? by Lila Abu-Lughod)

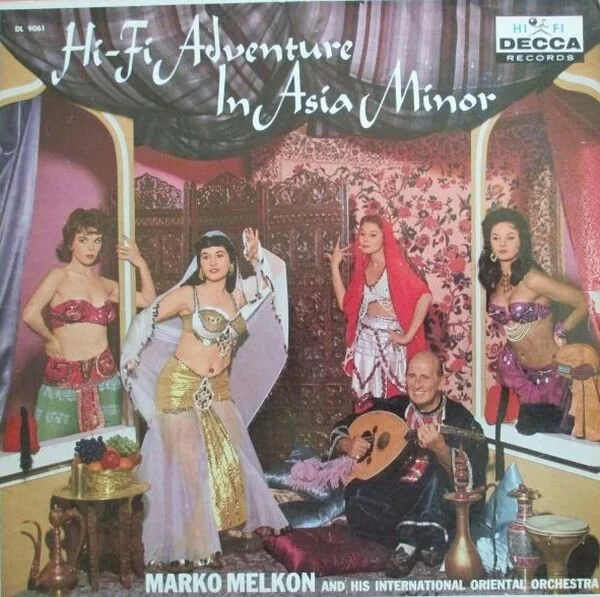

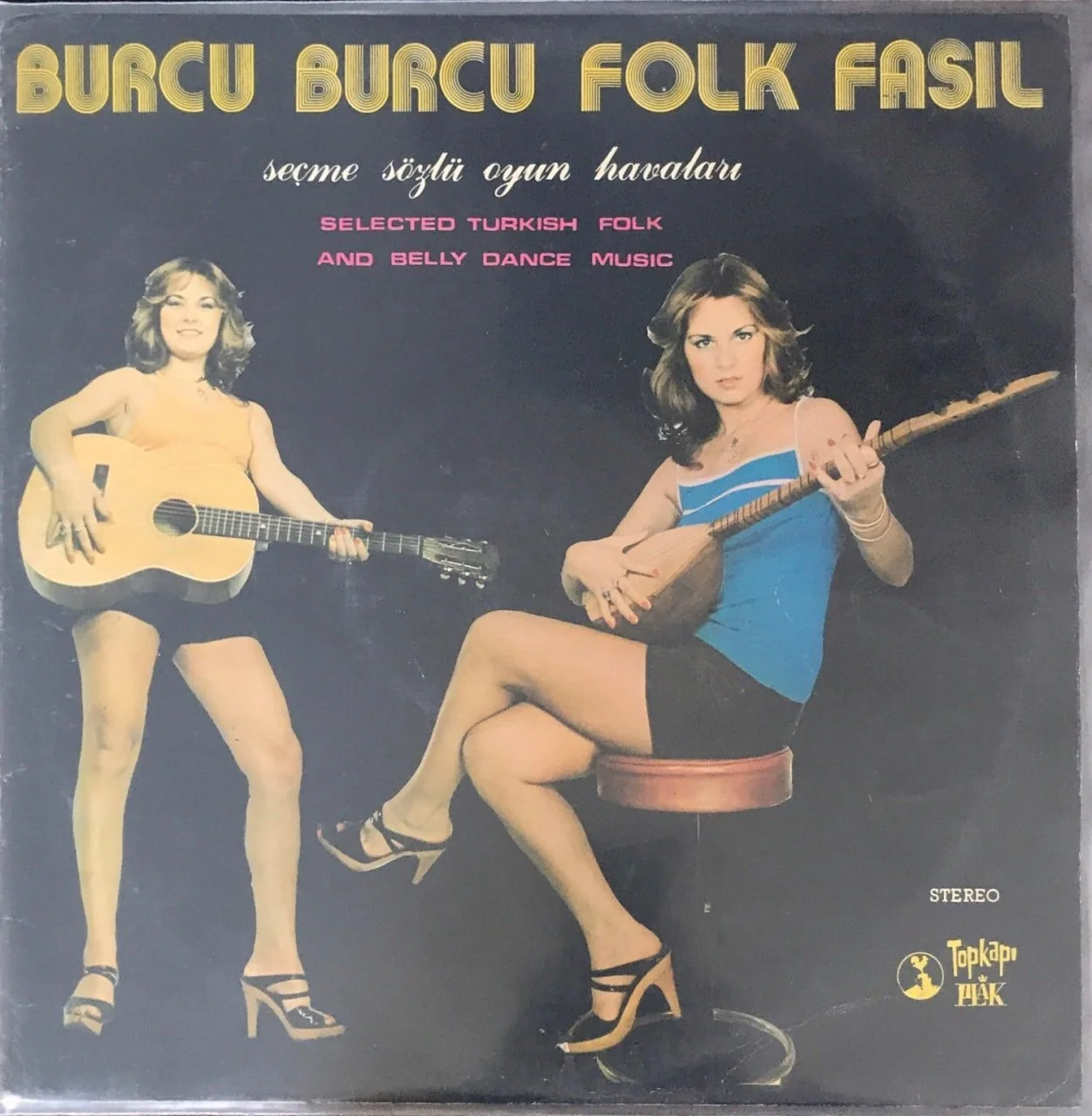

Assumptions and imaginings are common traps that people often fall into when they tried to understand and interpret Muslim cultures. Consider the “world music” industry that is highly influenced by the imperial and colonial narrative. In the context of Middle Eastern music, we see an exaggeration of décors, costumes, and performance. Popular culture takes advantage of this abstract knowledge about Middle Eastern cultures and reproduces the orientalist mindset and portrays the Middle Eastern people as exotic beings.

Images on the left: New York, New York. Turkish nightclub on Allen Street. (1942) Source: Library of Congress

Image on the right: The album cover of Marko Melkon and His International Oriental Orchestra (1958)

At this point, the question in my mind, specific to music, is how to interpret other musical traditions without being insensitive to performers and their community?

When I asked Dena how she finds the balance between these two traditions, she compared her ability to switch between styles with bilingualism:

"Maybe it's just like languages. If you speak Spanish, English, and Turkish, you might occasionally mix a few things, but you're pretty good at keeping them separate. Right? I think it's the same. The longer you've done it, the easier it is... To add more things, more languages, more instruments, or more styles. I love that I have a music theory background so that I can categorize things in a really simple way. That makes me ... go to the four, to the five or flat five, okay, or whatever. I have these ways that [it's] like a language to explain it.”[2]

Scholarly literature of ethnomusicology has a long tradition of reproducing Western categories to construct meanings, which ignores the fact that there are different, neither better nor worse, simple other ways of knowing things. Following Dena’s metaphor of language, ethnomusicologists can also put multiple epistemologies into conversation with one another. More than finding the right answer, the great endeavor of ethnographic research is to offer local meanings while remaining globally accountable. And as Dena says, the longer you've done it, the easier it is.

As a final thought, it is worth noting that our bodily experience is a source of meaning-making. Dena's emphasis on learning by looking at each other or closing our eyes validates the importance of investing in multi-sensorial skills. We may all agree that “meanings and experiences in the field are filtered and colored through sensations of the body,” but we must also accept that bodies are further shaped by gender, age, race, ethnicity, and class.[3] Although this seems to create a deeper separation among us, boundaries are not barriers but "crisscrossing sites" where we could discover identities, understand intersections, and celebrate our differences.

[1] Currently, the group has four members: Dena El Saffar (viola), Tim Moore (percussion), Tomas Lozano (guitar), and Cemal Silay (bağlama). Since the members of the group play more than one instrument, they also perform with other instruments such as oud, hurdy-gurdy, or joza. See their website here.

[2] Salaam Noon Concert, September 19, 2012, 20-052-F, Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN.

[3] D. Soyini Madison, Critical Ethnography: Method, Ethics, and Performance, 3rd ed, Los Angeles: SAGE, 2020:227